Mimi Bhalla

When I misbehaved as a child, my mother would suggest that I might be a Changeling. Her words were set with grim sincerity, as if seriously preoccupied that her baby girl might be gone, stolen in the night, replaced with an obscene imitation. At my indignation, she would double down until I was forced to shape up, to prove myself as her real daughter. Then she would acquiesce. She was only teasing, she would never let any wicked creature steal her child.

Raised on her Irish grandmother’s fairy tales and bedtime stories, my mother imparted to me her wisdom on the nature of the faeries, sparking my interest immediately with her hair-raising descriptions. Most children were led to believe in fairies as kind, sparkly friends—characters like Tinkerbell. Yet dial the clock back a couple centuries or so, to societies medieval, feudalistic, and fiercely superstitious, and fairy turns to faerie, benevolent to malicious.

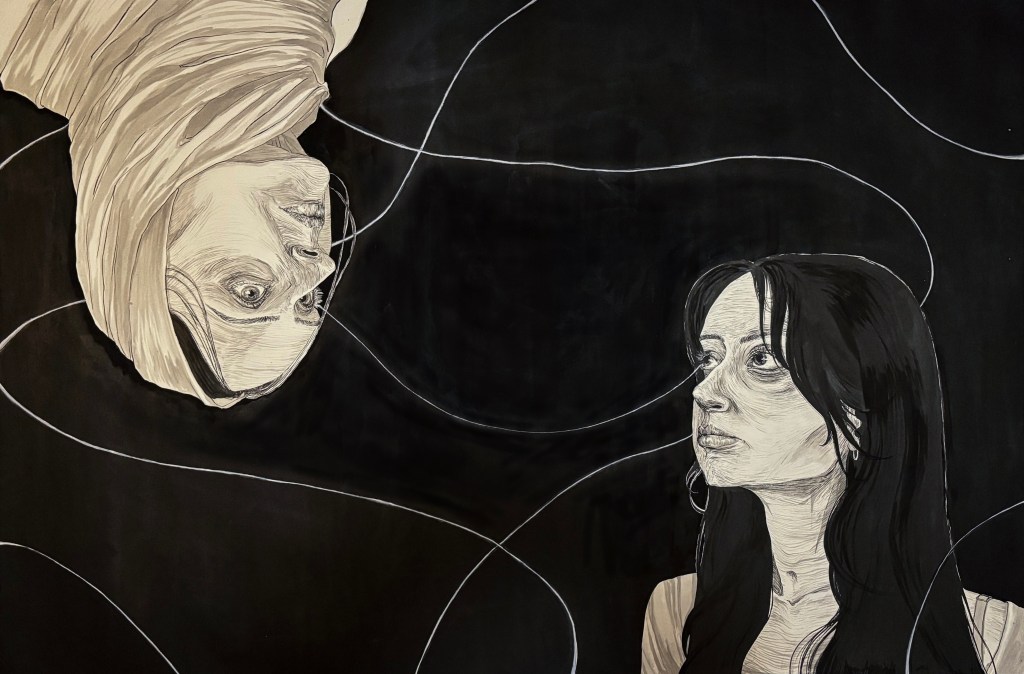

According to Irish, Germanic, and Norse legends, a baby left unattended by its mother may be abducted by fairies that replace it with a shapeshifting fae child. Their motives for the kidnappings were numerous: desiring the love of a human child, acquiring an obedient servant to raise, or taking vengeance against a human that crossed them1. Once the fairies captured their prize, they would leave one of their own babies in its place, aka the Changeling. The undercover Changelings could assume the physical form of the human child, but with limits: features such as abnormally small and skinny bodies, big heads, beards, dark eyes, and unholy appetites set them apart from their human counterparts2. While these features were meant to signify them as demonic, most of them actually mimic the features of malnourished or developmentally delayed children, not uncommon among poor rural populations experiencing famines. Once parents recognized these signs of the Changeling and realized the fairies had replaced their child, they were obligated to banish the Changeling in order to prevent its demonic influence from taking hold of the family3. As D.L. Ashliman puts it in his comprehensive essay, “Changelings,” the myth of the Changeling allowed struggling families to cut off an extra mouth to feed by believing their child to be “the offspring of some demonic being, offspring that could be neglected, abused, and even put to death with no moral compunctions.”4 Their beliefs, which we would deem inhumane today, assured the family’s survival across generations.

Joy Williams, American writer and Pulitzer Prize runner up, weaves a compelling new iteration of the dreaded creature in her 1978 novel, The Changeling. The novel follows the alcoholic young mother Pearl. Casting off her husband and ordinary civilization for a controlling new lover, Pearl comes to an isolated island inhabited by his relatives and a strange tribe of free-range kids. Here she bears her child, Sam. But this unusual homestead is too stifling—almost as if Pearl herself has been kidnapped into an inhuman, faerie world. After Pearl’s plane crashes in the midst of her first and only escape attempt, a seemingly predestined event, Pearl is separated from Sam in the rubble. Pearl’s baby, handed back to her in the hospital, is not the “right kind of baby,”5 with “tiny, sharp nails,”6 a face like a “mask’s”, and “black, blurred eyes.”7 While breastfeeding, he pierces her nipple with triangular teeth, sucking insatiably. Her mounting fears cause Pearl to declare, with an unshakeable certainty uncharacteristic of her, “‘You’re not my baby,’” and “‘You belong to someone else.’”8 Being a physical manifestation of her failures and a traumatic near-death experience, it is hard to say whether Sam was swapped out for a more sinister being by the will of the fae or if this is a conviction of Pearl’s own self-destructive paranoia. As her life on the island goes on, her paranoia overtakes her until she finally succumbs to the children’s needs and lets them possess her, mentally, physically, and spiritually. As the novel unravels in the jerky manner of a kinked hose, it becomes more and more difficult to decipher whether Pearl’s baby is unnatural or Pearl herself is unnatural, as she slips further into her deranged, alcoholic haze.

Pearl’s weak agency and spiritual depravity reflect her feelings of futility while contending with the ceaseless demands of motherhood. Motherhood, from Williams’ point of view, is no picnic, and the concept of the Changeling is no more than a manifestation of a flawed mother’s fears and desires. The Changeling paints a portrait of what happens when women become mothers before they’re ready, become mothers with no support system, become mothers when they’re still children themselves, or still discovering their inner child and her demands. Are children a punishment? A gift? Combining everything from the themes of adultery, the Puritanical attitudes towards sin and predestination, to the detail of Pearl’s name itself, The Changeling recalls the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne in his masterpiece, The Scarlet Letter.

Hawthorne’s Hester and Williams’ Pearl, though centuries apart, are linked by the same paralyzing doubts of motherhood. They live with the weight of their sin and its abominable product. By giving Pearl the same name as Hester’s daughter, Williams reinvents Hawthorne’s original Pearl into her Pearl. With the original Pearl all grown up, the vicious cycle of motherhood continues: like mother, like child. The Changeling uses literary tradition and the myth of the Changeling to present foreboding insight into how the sacred relationship between mother and child can turn ruinous, even parasitic.

The daughter and granddaughter of Protestant ministers, Joy Williams captures the religious undertones of divine mercy and retribution. Pearl’s Changeling child underscores her growing unfaithfulness. The setting itself is steeped in strict religious expectations— after being corralled back to the island from Key West, Pearl lives under the control of Thomas, a learned theologian with eccentric educational demands of the children. Pearl’s creeping uneasiness towards God is revealed through her impressions of religious imagery: the imprint of a cross like “a scar upon the dust,”9 something ancient and abandoned, like a wound closed up, which she fails to attach to. Pearl deems the religion “too carnal.”10 Her directionless spirituality views God as more “barbaric”11 and chaotic than good-willing and orderly, as she suspects that “God didn’t love human beings much…what He loved most was Nothingness.”12 Cynical but open-minded, Pearl’s less rigid approach to religion acknowledges dark forces and doesn’t impose limits to reality. Her approach falls more into line with the original Protestants, ones who would readily accept the possibility of a Changeling in their midst. Martin Luther, the religious leader of the Protestant movement, was a devout believer in Changelings himself who held “no reservations about putting such children to death.”13 With this religious backdrop in mind, Pearl’s Changeling child can be seen as a manifestation of her rejection of religion. Luther believed in punishment as a necessity to remove the presence of the devil; this Puritanical severity forms the base of our great American literary classics and reinforces the idea of children as a burden. As Pearl battles dark forces on the island, this underlying awareness of the devil signals that her battle is a losing battle, the challenges of motherhood too overwhelming to overcome.

As stated before, The Changeling draws parallels to another iconic literary work dealing with Puritans and Changelings: The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Williams’ Pearl is definitely a sinner— not only an alcoholic but an adulterer. Her actions echo those of infamous literary adulteress Hester Prynne, made to wear that scarlet A on her breast. Hester also conceived her child, coincidentally also named Pearl, by adultery. While Hester’s baby, Pearl, had certainly “no physical defect,”14 her “black eyes” contained an “unsearchable abyss,”15 her face looked “fiend-like,”16 and her laugh sounded “full of merriment and music.”17 These features are characteristic of Changelings according to Irish mythology, which claim above average intelligence and musical ability to be faerie traits18. In fact, “Hester could not help questioning at such moments whether Pearl was a human child. “She seemed rather an airy sprite, which…would flit away with a mocking smile.”19 Just as Williams’ Pearl renounced ownership of her baby Sam in the hospital, Hawthorne’s Hester cries, “‘Thou art not my child! Thou art no Pearl of mine.”20 While Williams and Hawthorne are clearly hinting at a demonic possession, neither author definitively tells the reader whether these mothers’ fears are grounded in reality or paranoid delusion, allowing us to guess for ourselves. The reflection of Pearl’s name in Hester’s child muddies our perception further. It seems almost as if Williams’ Pearl is a continuation of Hawthorne’s Pearl, a shape-shifting Changeling herself. The continuity across literary works, a sequence of Pearls across generations, shows us the intergenerational consequences of becoming a mother without the adequate resources of handling motherhood. The result damages not only Pearl, but her relationship with her child, and the child itself.

Pearl’s lack of connection to her child is exacerbated by a lack of connection to herself. Pearl has no idea who she is, as she doesn’t feel like “a real person.”21 Being a real person seems to be defined by making decisions, so Pearl attempts to make drastic choices to establish some sense of identity. Describing the shoplifting episode that led to her meeting Walker, she feels that “She wanted to do something she had never done before and in that way discover something about herself.”22 Successfully, this decision catalyzes the major life events of moving, taking a new lover, and having a child. But even as she allows these events to unfold, she feels like she took no agency in making them happen, reflecting to Walker, “Why am I with you know? I didn’t have to follow you.”23 Walker, preying on her uncertainty, claims her, reassures her that she’s a “pretty piece of glass on the beach, a piece of driftwood… washed up by the tide.”24 His to collect. Drifting through her life on the island, feeling like she doesn’t belong among the world of the adults or the children, Pearl allows alcohol to lull her into complacency. While she doesn’t conform to religion, which may be thought of as choosing not to think for yourself, Pearl instead decides not to think at all. Paradoxically, her decision is to not make decisions.

The image of the Changeling extends Pearl’s lack of ownership of her identity. She cannot even take control over her own child or other children, confessing to Walker after her first year at the island that she feels that her “soul is gone now…all those children have it in some way.”25 Pearl spends days, weeks, years by the pool with them, and if she tries to get up, the clamor of voices after her: “‘don’t go, where are you going?’”26, tugging her hand, pushing her back into her pool chair, “breathing on her with their sweet breaths.”27 The children’s ravenous appetite for her is more than material but spiritual, her emotional labor of tending to their needs and whims leaving her exhausted, “a bruised reed.”28 And yet, the children are Pearl’s only allies. As Pearl mentally spirals, the line between childhood and adulthood becomes fuzzy, “her world and theirs were very close.”29 The island’s flashing images impressed on her mind: “The scorched grass and the children’s sweat and her own,”30 the sea “fat and high from the rain.”31 The world of the children’s imagination merges with her own: stories like “the beginning of the world, full of chaos and warring seeds,”32 stories of wonders like whales “galloping toward one another through the impossible depths of the sea.”33 Williams places us in a world shifting and undefinable, where the line between reality and imagination is blurred, whether through the children’s eyes or Pearl’s alcoholic filter. The novel recalls to us the innocence of children, “their sparkling points of incorruptibility like the shapes of the stars just now blossoming in the heavens.”34 Ultimately, we come to pity Pearl for the childhood that was robbed from her, the motherhood that was thrust upon her. We understand her delirium on the island as a misplaced attempt to get back to her inner child, her original form, the outer layers peeled away until all that remains is her purest self. We pity Sam for his status as the Changeling and his blameless role in her resentment. This relationship between mother and child/Changeling emphasizes the bestiality of our nature, reminding us that we are animals, “mouths full of meat, the eternal consuming the corruptible.”35

In The Changeling, Williams challenges the idea that children are a blessing. And for that reason, Williams’ message only becomes more relevant as her work ages. A record number of young women are considering the option to not have children, an option that seemed inconceivable for their mothers and grandmothers before them. No more do societal norms force women to reproduce and reproduce, to exist in a semi permanent state of pregnancy, to endure physical changes and horrible tragedies of children lost to unfavorable circumstances. The motif of the Changeling is a distant memory but a haunting reminder of the innate evil that lies dormant in us, the horrors of what we are capable of creating and capable of acting when pushed to desperation. Pearl teaches us through her experience: don’t be a piece of driftwood, don’t take on more than you can handle. But to be merciful to Pearl, she also dares us to succumb to our inner magic. The Changeling rediscovers the child hidden in each of us, sucked down into us by adulthood demands, and reclaims our base animalistic desires. The children have “the warmth of night in their coats,” transmuting forms, transmuting into animals like “little flowers,” “little stars with their past lives flickering,” licking her clean36. With their essence of flowers and stars and cherishable innocence, the children teach us. They can access the pure core of our identities, untainted by outside pressures and influences. They can bring us back to the titillating delusions of possibility–as long as we choose to be them rather than to have them. The Changeling is a life-changing, all-consuming read, warping our perception like a funhouse mirror and taking us on a journey through a dreamlike semi-consciousness, a picturesque Neverland-ish scene. One almost wouldn’t mind being kidnapped by fairies themself, with a Changeling left in their wake, if it meant accessing their fairytale world.

Footnotes

1. “Exploring Irish Mythology: Changelings,” last modified December 22, 2021, https://www.irishpost.com/life-style/exploring-the-irish-mythology-changelings-170347.

2. “Changeling Mythology | History, Characteristics & Examples,” last modified February 5, 2023, https://study.com/academy/lesson/changeling-mythology-history-folklore.html.

3. “The Enduring Legend of the Changeling,” last modified March 1, 2018, https://skepticalinquirer.org/exclusive/the-enduring-legend-of-the-changeling/.

4. D.L. Ashliman, “Changelings: An Essay,” University of Pittsburgh (1997).

5. Joy Williams, The Changeling (Tin House Edition. Portland, Oregon: Tin House Books, 2018), 90.

6. Williams, The Changeling, 90.

7. Williams, The Changeling, 89.

8. Williams, The Changeling, 91.

9. Williams, The Changeling, 245.

10. Williams, The Changeling, 84.

11. Williams, The Changeling, 173.

12. Williams, The Changeling, 84.

13. D.L. Ashliman, “Changelings: An Essay,” University of Pittsburgh (1997).

14. Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter (Dover Thrift Editions. Newburyport: Dover Publications, 2012), 61.

15. Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter, 67.

16. Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter, 66.

17. Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter, 63.

18. “Changeling Mythology | History, Characteristics & Examples,” last modified February 5, 2023, https://study.com/academy/lesson/changeling-mythology-history-folklore.html.

19. Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter, 63.

20. Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter, 67.

21. Williams, The Changeling, 24.

22. Williams, The Changeling, 25.

23. Williams, The Changeling, 32.

24. Williams, The Changeling, 32.

25. Williams, The Changeling, 74.

26. Williams, The Changeling, 183.

27. Williams, The Changeling, 113.

28. Williams, The Changeling, 266.

29. Williams, The Changeling, 153.

30. Williams, The Changeling, 151.

31. Williams, The Changeling, 195.

32. Williams, The Changeling, 154.

33. Williams, The Changeling, 168.

34. Williams, The Changeling, 290.

35. Williams, The Changeling, 299.

36. Williams, The Changeling, 300.

Works Cited

Ashliman, D.L. 1997. “Changelings: An Essay.” University of Pittsburgh. 1997. https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/changeling.html#legends.

“Changeling Mythology | History, Characteristics & Examples.” Study.com. February 5, 2023. https://study.com/academy/lesson/changeling-mythology-history-folklore.html.

“Exploring Irish Mythology: Changelings.” The Irish Post. December 22, 2021. https://www.irishpost.com/life-style/exploring-the-irish-mythology-changelings-170347

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. 2012. The Scarlet Letter. Dover Thrift Editions. Newburyport: Dover Publications.

Kreidler, Marc. 2018. “The Enduring Legend of the Changeling.” Skeptical Inquirer, March 1, 2018. https://skepticalinquirer.org/exclusive/the-enduring-legend-of-the-changeling/.

Williams, Joy. 2018. The Changeling. Tin House Edition. Portland, Oregon: Tin House Books.