Sarah Rizvi

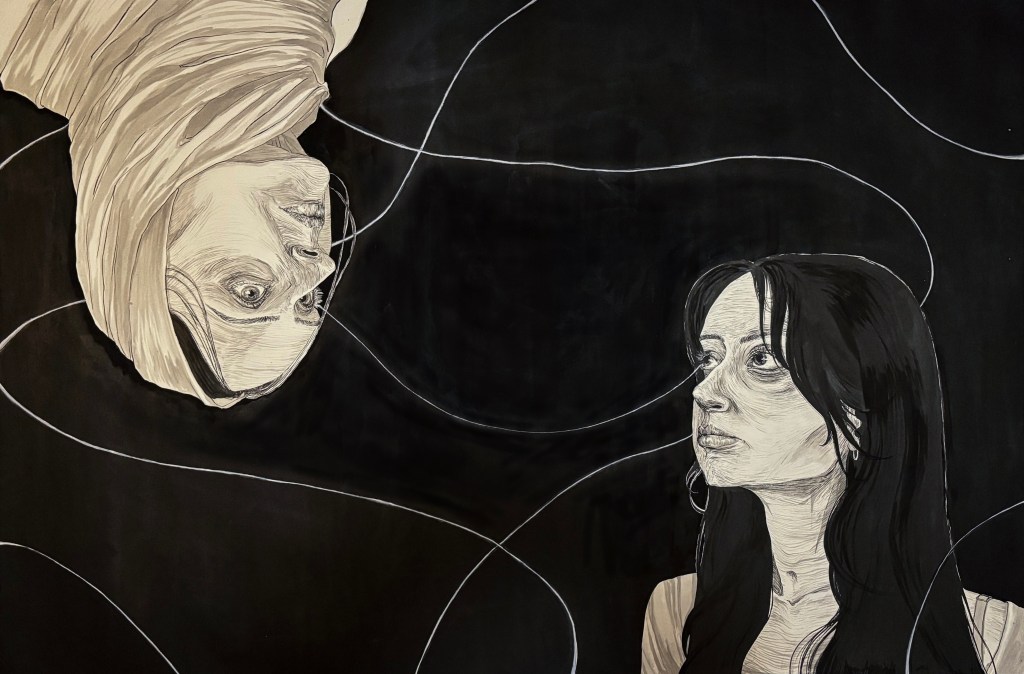

Modeled after “The Father From China” in China Men by Maxine Hong Kingston.

I have watched you beg, Mother.

You would say please after every request you had for my father, “Can you wash the dishes today, please?”, “Will you bring me some water, please?”, “Can’t you be nicer today, please?”, and each “please” would be more desperate than the last. You would ask with a casual smile on your face, but I could see the way your eyes widened slightly, quivering with the effort to keep your emotions from spilling out. And after every “no” you got in response, I would watch your face fall further to the ground with every passing day. Sometimes you would sink to the ground and mutter streams of Arabic with your eyes closed, and I would sit beside you and try to copy the sounds as if to multiply the effectiveness of your prayer. You would turn to me and drape the long end of your headscarf over my head, and you would correct my gibberish pronunciation by moving my mouth and squeezing my cheeks. I would laugh and start running around with you playfully running after me, and we’d soon be joined by my three older siblings, a big game of tag.

But often, you would stay sitting and the Arabic would get more and more intense, faster, and you wouldn’t wipe your tears. They ran down your face and left damp spots on the collar of your kurti that would grow larger until the bright green of the cloth would darken into a soggy moss color. You would scream if I interrupted you, and I would run upstairs and hide with my ears covered, until my siblings would find me and distract me with the special art supplies that they only took out for school projects. My eldest sister played the token obedient role of the eldest daughter in an immigrant family. She was a second mother to me. Mother, what you could not do for us, she did. We learned how to make friends properly, what jokes were appropriate and what weren’t, what family stories we could safely share and which ones would result in the

downfall of our family. At the time, I didn’t understand what she meant; how could our family get lower than we already were?

I remember the first day you put a hijab on me. I was seven years old, and at the time, the idea of hijab seemed far away, too adult for a child like me. You told me, “You’re a woman now.” Despite the Islamic required age to wear hijab being nine, you deemed me ready enough two years earlier. I felt the prickly feeling of discomfort in the pit of my stomach. Everyday, each wrap of the cloth around my head amplified the suffocating feeling. The first day I went to school with my hijab on was jarring. The same classmates who would sit next to me, talk to me, play with me, were suddenly strangers. The experience of watching the people who I thought were my friends start to look at me with fear and disgust was one that I would never forget. In their eyes, the cloth on my head was a label, I was now visibly Muslim, someone to be scared of. Mother, the same cloth that gave you freedom was what had chained me to a role I wasn’t ready to live yet.

One time, you caught my brother talking to a girl (a crime worse than anything for a Muslim family,) and you dumped orange gatorade over his head and locked him in the backyard for three hours. I watched from my place under the kitchen table as the backyard door rattled and shook with my brother’s punching and kicking, his angry face distorted by the cloudy glass of the door. You had your back to the door with tears in your eyes, as if looking at your son would break the strained thread of control you had. You let him back in the house right before my father came back from work. You said, “Don’t say anything to Baba, he will send you to India for this.” Your punishment was always only a small taste of the anger of my father. This was your way of being merciful, your way of protecting your only son from the wrath of his father, something you yourself could not escape.

There was a day that you could not act fast enough as a shield between my brother and my father, a day etched into my memory. Earlier that day, my brother and father had started their usual bickering about a topic I do not even remember. As usual, the argument spiraled onto bigger issues, issues that had been boiling beneath both of their skins, straining in their popped veins and white knuckles. It was a bizarre sight to watch from the safety of the stairs, the banister acting as a shield between me and the chaos, an eighteen year old boy looming over a 48 year old man, the same anger reflected in both of their eyes. When my brother’s fist made contact with my father’s face, I don’t remember my father’s reaction, I remember my eyes darting to you, Mother. You were pleading with them, crying for them to stop amidst the mayhem of the scene; a chair was thrown across the room, there were repeated thuds of fists beating on a back, slurred curse words so gruff and tense that I couldn’t even recognize the voices. It was strange to watch you so desperately protect the two people responsible for your irreversible sadness. I watched as my brother sprinted to the phone and dialed 911, saying “My dad is crazy, my dad is crazy” over and over. Before the ambulance arrived, my sister grabbed me and told me frantically, “Don’t say anything bad about Baba, no matter what.” There were two officers, a man and a woman; I remember both of them smiling at me and I tried to smile back the best I could, but my face felt like it had been dipped in ice water, my mouth too stiff to follow the directions I was giving it. The woman sat me down on my bed, and I rehearsed my lines in my head. I was ready to get into my script, but her first question was just “How old are you?” to which I said, “eight..” and she smiled again. I didn’t attempt to smile back. She reached past me to the picture my sister had quickly hung onto the pole of my headboard, a picture of me and my dad. She asked, “Is that you and your dad?” and I thought about how stupid she must be to not know when she had just seen him downstairs, but I answered obediently with a nod and a quiet “yes.” I was waiting for the question, the one where I would have to say my lines, but she just patted my hand and said, “it’s a lovely picture.” I wondered why the officer had not asked me anything about you, Mother. But I suppose I wouldn’t have known what to say, anyways. I only remembered the proper etiquette

you had drilled into my brain after the officer had already left the room, so my belated “thank you” was met by the closed door.

Sometimes, you would talk about your family back in India, your father, your sisters, and rarely, your late mother. I would listen closely because it was the only time you would smile your real smile. You told stories of your father’s education, how he was the top of his class and how his older brother was a famous speaker. I would sit and imagine my Nana, grandfather, through the stories. I remember in particular how your face would light up with pride when you told me about how his university had given him a plaque to honor his years as a professor. Your face would dim slightly when you talked about your mother though, with a longing I could see even at my young age. I would hear the pain in your voice mixed with the happy nostalgia of your short memories with her. There were only a few stories about her and they lacked the detail Nana’s stories had. You would mention her cooking, her fashionable clothing, the way she loved your father, but when I asked about what she looked like, you would get quiet and I would know to change the topic. Sometimes I would listen to you talk about the Jinn that supposedly roamed your courtyard, and I would get so scared that I couldn’t sleep at night thinking about it. The image of dark spirits listening in on me, watching me, haunted me for years, and at times, I felt like I could see them out of the corner of my eye at night. I was afraid they could see my thoughts, the ones I kept not only from you, but Allah too. I wondered if the Jinn would side with me, with my rejection of faith, or if they were really secretly devout and would rat me out to our god. But more than Allah, I was afraid of you finding out, Mother. But my thoughts would get cut short when we would hear the thud of a car door shutting and the jingle of keys in the front door. The abrupt silence was my signal to run upstairs, cover my ears, and wait. When my mother was born, her father was so disoriented that he wrote “baby girl” on her birth certificate where her name should have gone. For 6 weeks, my mother’s official name was Baby Girl. She was the first daughter, so she was pampered and coddled only up until her sisters were born, and then her child status was taken from her, replaced with “Apa,” urdu for older sister. My mother was allowed to experience the joy of being a child for a total of nine years, until the day her mother had a heart attack. Everyone in the family worked fast and rushed her into a car, but the traffic and unforgiving roads of India killed her before they could even reach the hospital. My mother was left with the burden of being the caregiver of her family at nine years old since, supposedly, it was a role no man could ever take. My mother says she chose to step up on her own, but the version I know is much more believable than hers.

***

My mother was left motherless at nine years old and her father was so crippled with grief that he took her own right to grief away from her and replaced it with the weight of maintaining a family all by herself. She played the role for seven more years until her name was signed onto a document, tying her to a man twice her age. Her father knew the man from his years working as a professor; he was the top student in Nana’s class, and his academic prowess was apparently enough of a qualification to take my mother’s childhood away from her. She was told she would get gifts and get to see the grand life of America, so she happily agreed, unbeknownst to the manipulation she was being faced with. At sixteen, my mother met my father for the first time at her own wedding and was across the world by the next day.

My mother’s first impression of America was the airport security’s “random” check, a story I would hear for years before every flight, our family’s token cautionary tale. They made her remove her hijab and interrogated her in a room for three hours. They asked her questions and dissected her life. She slipped up by saying her real age, sixteen, instead of her new age which was now twenty one, but got away by saying she was just tired from the flight. (If they found out a sixteen year old was traveling with her thirty one year old husband, there would have been bigger problems than just getting into America.) They used her broken English as a weapon, telling her she would need to work on becoming more American if she wanted to live here for the rest of her life. She was given question after question and lectures about America and what was deemed too “cultural” about her, and they let her go only after they had stripped her of the little dignity she had brought with her from India.

My mother’s experience of marriage started out the way a teacher and student’s relationship might be. Her husband, a thirty one year old man, spent a year learning the strengths and weaknesses of his wife, and took notes on what she should improve on, be better at. My mother was never treated as my father’s equal. But it wasn’t all that surprising to see an adult unable to see a child as his equal. At seventeen, my mother gave birth to a son. A mother at last, she had a new purpose for her life. She devoted her every living moment to raising her son, to make sure he was not motherless the way she was. The age difference between my mother and my brother is the same as the one between her and my father, and that must have explained why her son grew up to be a monster, just as my father was.

My mother gave birth to three more children, all girls. For every birth after her son’s, she was alone at the hospital, gripping the nurse’s hand as she pushed out another purpose to live. After hours of giving labor, my mother would drive home and make dinner for my father, and he would eat without guilt. When my father wouldn’t be yelling at my mother, my brother would. My father and brother were constantly at odds with each other; their differences and issues with each other grew more and more, but their one connection was their shared abuse of my mother. Bigger and more muscular now, my brother would often get violent. Once, my mother scolded him for not studying for his SATs when he was supposed to, and in a fit of rage, he pushed her and she fell and cut her arm on the counter. My father, in his usual place in the garage, ran into the house after hearing the noise and, happy for an excuse to be angry with his son, for the first time, my father was angry for my mother instead of at her.

At 35 years old, my mother’s hopes were slowly disappearing one by one, so she did the one thing she knew how to do: pray. She prayed at every given moment, and when she wasn’t praying she was thinking about what to pray for next. Her devotion to religion gave her a crumb of renewed motivation, and she became a well known reciter at the mosque. The mosque was the one place she could put on a facade of being put-together, the mask of a perfect family. Her practiced smile and script was always so polished that it would even convince me at times. But the ride home from the mosque would rid me of all those thoughts; her perfected act would drop almost immediately, replaced by her usual dim gaze. But slowly, the dimmed light behind her eyes began to flicker again. Her visits to the mosque and her mosque friends’ houses would keep her busy, distracted from the reality that waited for her at home. The same faith that had driven me away from my mother was keeping her alive. The prayers may have fallen on deaf ears, but my mother’s devotion to religion gave her a new purpose, one that couldn’t grow up and turn on her like the previous ones had.

My mother turned 36, and 37, and 38, but also 41 and 42 and 43 (legally), and she continued her praying though she saw no changes for the better in her life. Religion was my mother’s fixation; it came with a community of people, a hope for something better, and she thrived in the fact that religion wasn’t a definite thing. The unsurety of religion was key to her passion for it; it could never hurt her the way a human being could. But religion could not stop the passage of time. My mother watched as her children grew older and moved away, and her ache for family grew more and more painful. She spent each day the same, fulfilling her daily tasks demanded from her by my father without complaint. Her silent obedience was her resignation to the role given to her 22 years before. Her hobbies were childlike; the life she could not live in her youth she tried to replicate in the little pockets of time between my father’s demands. But despite the appearance of my mother’s inner child, she was undeniably getting older. Her face had begun to sag and her bones were colder. The weight on her frail shoulders grew heavier by the day, it was as if the ground was pulling her to it, waiting for her to sink down to her knees and resume her position beneath everyone else. But still, my mother remained upright, barely, but surely, alive.

Sarah Rizvi is an aspiring writer and artist who draws inspiration from her culture as an Indian Muslim woman. Through her writing, she wishes to portray the importance of the uniqueness of stories rather than catering to a universal outlook of cultural experiences. Rizvi’s focus on family is reflected in much of her work and emphasizes the complexities of having familial struggles paired with unbreakable bonds. As she writes, Rizvi hopes to continue to put her experiences into words that resonate with others.

Leave a comment